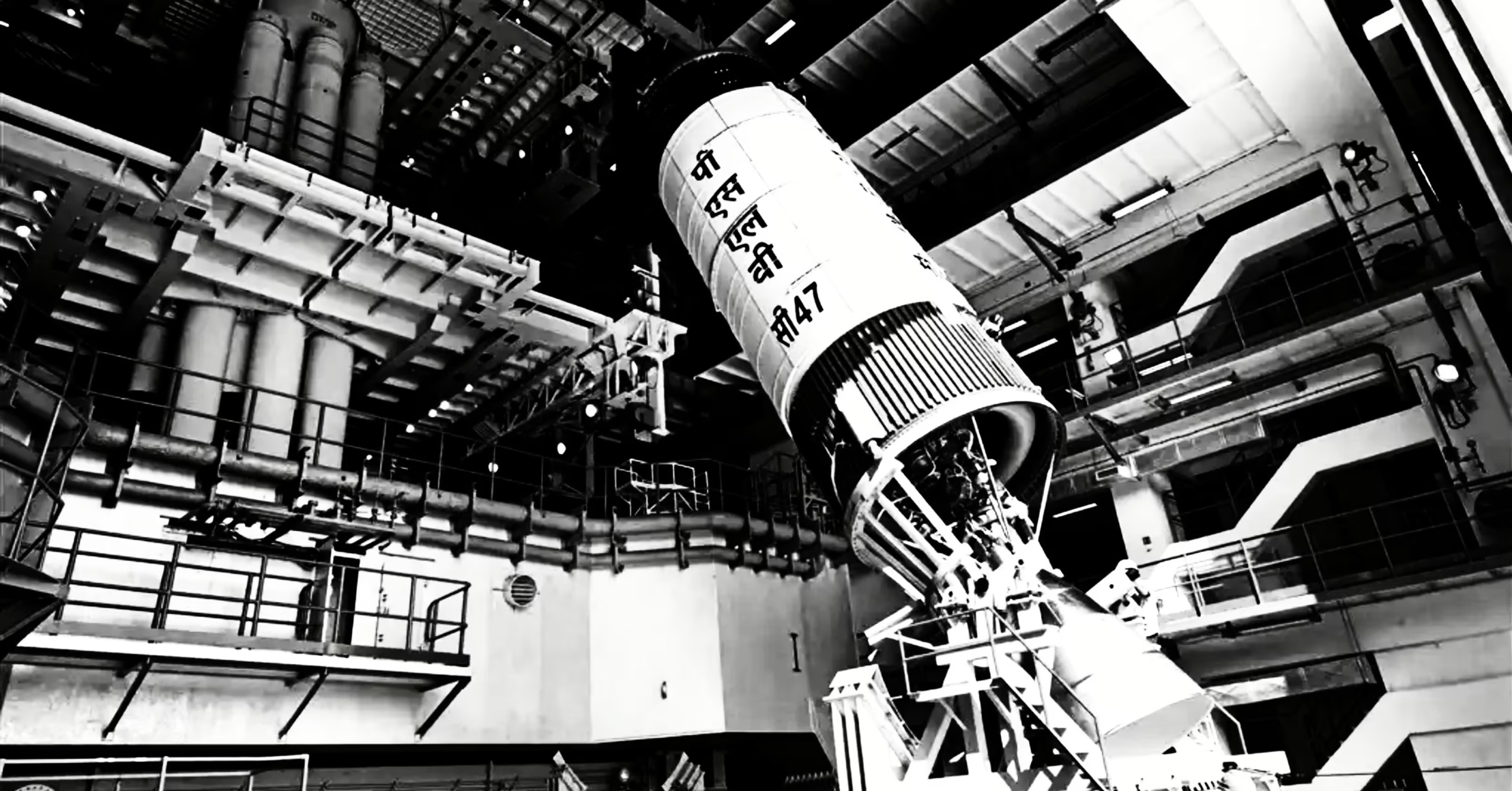

Advt. No. 17556/HR/All-India/2025/2

Are you an engineering graduate from Electronics, Mechanical, Computer Science, or Electrical branch looking for a high-profile job in defence electronics? This one could be it. BEL has released one of its major drives for Probationary Engineers in E-II Grade, offering lucrative pay, prestige, and the kind of work that matters. This guide gives you everything: eligibility, preparation strategy, timeline, FAQs, and what it all really means.

What is the role?

Position: Probationary Engineer (E-II Grade)

Organisation: BEL, a leading Navratna Public Sector Undertaking (PSU) under MoD, specialising in defence electronics, radars, EW systems, aerospace electronics, naval systems, etc.

Vacancies: Across four core engineering disciplines – Electronics, Mechanical, Computer Science, Electrical.

Grade & Pay: E-II Grade Officer – approximate CTC around ₹12-14 lakhs per annum, + allowances, etc.

Why it matters: This is entry-level officer cadre (not workshop, not diploma level) – for fresh engineering-graduates to join the major defence electronics flagship company of India.

Vacancy distribution & pay details

| Discipline | # Posts | Key Points |

|---|---|---|

| Electronics | ~175 | Largest share |

| Mechanical | ~100+ | Heavy engineering systems |

| Computer Science | ~40-50 | Software/firmware focus |

| Electrical | ~10-20 | Power/electrical systems |

Exact numbers may vary by the official notification & category; candidates should refer to the PDF.

Pay scale: ₹ 40,000 (starting) to ₹ 1,40,000 (with increments) in E-II grade.

Post-probation: After one-year probation, confirmed as Engineer E-II.

Who can apply? – Eligibility

1. Educational qualifications

- A full-time 4-year engineering degree (B.E./B.Tech) or equivalent in the specified discipline from recognised institute/university.

- For UR/OBC/EWS: “First Class” required (typically ≥60% aggregate) unless otherwise specified.

- For SC/ST/PwBD: “Pass class” may be acceptable (check notification).

- Disciplines specified exactly:

- Electronics / Electronics & Communication / Communication / Telecommunication

- Mechanical Engineering

- Computer Science / Computer Engineering

- Electrical / Electrical & Electronics

- If your branch is NOT exactly in the list (e.g., Instrumentation, Mechatronics etc.), your eligibility might get rejected.

- Final-year students: Many BEL drives allow “final year appearing” provided result declared before joining; check the notification.

2. Age criteria

- For UR/EWS: Up to 25 years as on specified date.

- Relaxations apply: +3 years for OBC-NCL, +5 years for SC/ST, additional for PwBD and Ex-Servicemen as per norms.

3. Other conditions

- Indian citizen.

- Must meet medical fitness, training span, transferable posting across India.

- No dual-specialisation, no “other equivalent discipline” unless explicitly allowed.

Selection Process & Exam Pattern

1. Stages

- Online Examination (CBT or OMR) – Technical + Aptitude/Reasoning + General Awareness (defence electronics context)

- Interview – Technical deep dive + HR / behavioural fit

- Final Merit List – Typically combined score (e.g., 85% Written + 15% Interview) – category-wise merit list.

2. What to expect in the written test

- Technical portion: Branch-specific core subjects (signalling, embedded systems, circuit theory for Electronics; manufacturing, thermo, fluids for Mechanical; algorithms, OS for CS; power systems, machines for Electrical).

- Aptitude: Quantitative, logical reasoning, English comprehension.

- General awareness & domain insight: Basic defence electronics, PSU environment, latest tech trends.

- Time management & accuracy are key.

- Negative marking: Some PSU exams do have negative marking – check notification.

3. Interview focus

- Your final year project or major internship – know it inside out.

- Defence electronics interests, understanding of BEL’s domain (radars, EW, aerospace systems).

- Behavioural questions: transfers, mobility, PSU mindset.

- Technical depth: Be ready to answer circuit diagrams, logic flow, mechanical design questions etc.

Application Process & Important Dates

- Apply Online Only via BEL official careers portal.

- Start Date: (As per notification)

- Last Date: (As per notification) — ensure time-zone, server crowding.

- Application Fee: Usually specified (General/OBC category pay, SC/ST/PwBD often exempt).

- Steps:

- Register with email/mobile

- Fill form fields (education, branch, category)

- Upload scanned documents (degree, marksheets, category certificate, PwBD if any)

- Pay fee (if applicable)

- Submit & download acknowledgement/print copy.

Note: Keep your degree, semester marksheets, and photo identity ready well in advance.

Preparation Strategy & Tips

1. Phase-wise plan

- Phase 1 (Weeks 1-4): Revise core fundamentals of your engineering discipline — pick 6–8 high-weight topics.

- Phase 2 (Weeks 5-8): Start practice papers of BEL/defence PSUs + timed mocks. Focus on speed & accuracy.

- Phase 3 (Weeks 9-12): Interview preparation — prepare project summary, defence electronics domain facts, and behavioural responses.

2. Discipline-specific focus

- Electronics & EEC: Digital logic, microcontrollers, signal processing, embedded C, VLSI basics.

- Mechanical: Manufacturing processes, machine design, thermal systems, fluid mechanics.

- Computer Science: Data structures, algorithms, OS, DBMS, programming logic, software design.

- Electrical: Electrical machines, power systems, control systems, measurement, PRACTICAL wiring & protection concepts.

3. General tips

- Solve previous year BEL question papers or similar PSU papers.

- Make a list of “BEL domain keywords” (radar, EW, aerospace, nav-systems) and read latest news.

- Interview: practise explaining your project in 2-3 minutes, then dive into details.

- Time management: In CBT you may have ~100 questions in 90 minutes, so ~1 min/question average.

- Stay Final Year candidate-aware: If your degree result is pending, obtain result declaration letter or backlog clearance.

FAQs & Important Clarifications

Q1: Is GATE score required?

No – this drive does not mandate GATE. Direct recruitment from engineering degree.

Q2: Can I apply if I’m in final semester and result awaited?

Often yes if the notification allows “result awaited” and you can furnish the degree at joining. Check the fine print.

Q3: What if my branch is “Instrumentation Engineering” or “Mechatronics”?

Unless explicitly listed under “equivalent disciplines”, branches not mentioned may be rejected. Apply only if your discipline matches exactly.

Q4: Is there training/bond period?

There may be probation of one year and confirmation thereafter. Check the notification for bonding clauses.

Q5: Are international or foreign institute degrees valid?

Only if UGC/AICTE recognised and reservation norms apply. Check the notification for equivalence clause.

Why You Should Apply

- Join a prestigious defence-electronics PSU with national importance.

- Roles are technically challenging – you’ll work on radars, missiles, aerospace systems, high-end electronics.

- Good starting salary + growth in officer cadre (E-II → E-III → etc.).

- Transferable all-India postings – excellent exposure.

- Great platform for young engineers to launch meaningful careers, not just jobs.

Final Checklist Before Submission

- Ensure your branch exactly matches the listed disciplines.

- Verify First Class / Pass criteria as per your category.

- Check your age eligibility carefully.

- Keep degree certificate/marksheets ready in digital form.

- Fill the online application well before the deadline — save the acknowledgement print.

- Start preparation early — technical + aptitude + mock tests.

Final Thoughts

The BEL Advt No. 17556/HR/All-India/2025/2 is a golden opportunity for young engineers aiming for a secure, respected, and technically rich career path. It’s not just a job — it’s a portal into the heart of India’s defence-electronics ecosystem. If you’re motivated, disciplined, and ready to invest in preparation, this could mark the launch of your professional journey.

Apply confidently, prepare smartly, and make your engineering degree count.

.

. .

.